Hidden Plastics: The Problem We Can’t Always See

When we think of plastic pollution, most of us picture the obvious: grocery bags tangled in trees, foam cups littering sidewalks, bottles bobbing in the ocean. But the truth is, the problem runs much deeper. A significant portion of the plastic polluting our world is invisible to the eye—either embedded in everyday items or broken down into microscopic fragments—and it’s everywhere.

Many of the products we use daily contain plastic, even when they don’t look or feel like it. Sometimes it’s part of the material itself. Other times, it’s hidden in coatings, adhesives, or fibers.

The Hidden Plastics All Around Us

Here’s a list of everyday items that often contain hidden plastics:

- Clothing (especially polyester, nylon, spandex, and acrylic fabrics)

- Tea bags (often sealed with plastic or made from nylon mesh)

- Disposable coffee cups (lined with polyethylene)

- Receipts (often coated with BPA-containing plastic)

- Chewing gum (the “gum base” is usually synthetic rubber or plastic)

- Wet wipes and diapers (made with plastic fibers)

- Glitter and sequins

- Paints and coatings

- Paper plates and bowls (typically coated in plastic for waterproofing)

- Bandages and medical tape

- Feminine hygiene products (pads and tampon applicators)

- Frozen food packaging (may contain plastic films)

Once you start noticing, it’s hard to unsee: plastic is embedded in our lives in ways we rarely consider. And because many of these plastic items are used only once, they contribute to a growing global plastics crisis that can’t simply be recycled away.

Microplastics: Tiny Particles, Big Problem

Microplastics are plastic particles less than 5 millimeters long—about the size of a sesame seed or smaller. They’re created when larger plastic items break down through sunlight, weather, and friction. Others are intentionally manufactured at this size for use in products like exfoliating scrubs or industrial abrasives (these are known as primary microplastics).

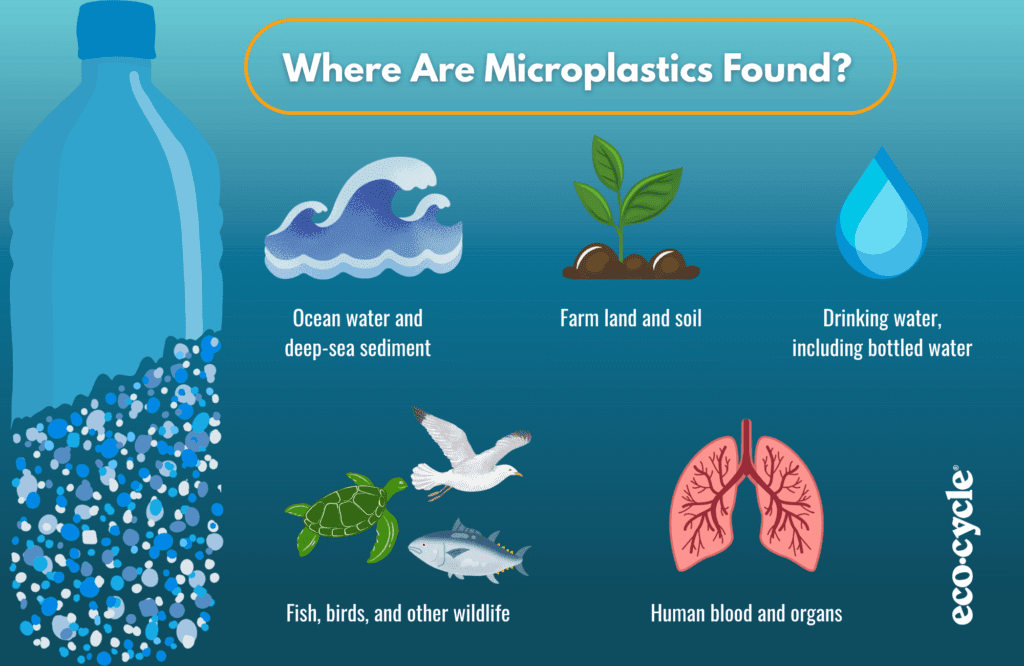

Microplastics have been found in:

- Ocean water and deep-sea sediment

- Soil and farmland (often through plastic mulch or sewage sludge)

- Drinking water and even bottled water

- Human blood, lungs, and placentas

- Fish, birds, and other wildlife

Microplastics are concerning not only because of their prevalence, but also their toxicity. They carry harmful chemicals and can potentially lead to DNA damage, organ dysfunction, metabolic disorder, immune response, neurotoxicity, as well as a variety of chronic diseases. Microplastics can also accumulate up the food chain, with wildlife often mistaking them for food, which can lead to starvation, internal damage, or poisoning. And humans are affected, too. Studies estimate that the average person inhales about 5 grams of microplastic per week—roughly the size of a credit card.

Systems Change: Policy and Innovation

The scale and reach of microplastics pollution can feel overwhelming, but there’s progress. Some microplastics have already been restricted or banned. In 2015, the US passed the Microbead-Free Waters Act, which banned plastic microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics like facial scrubs and toothpaste. Other countries—including Canada, the UK, and several EU nations—have passed similar or stricter legislation, targeting glitter, industrial microplastics, and synthetic fibers.

Beyond bans, innovation is emerging from both tech and nature-based solutions:

- Biodegradable materials are being developed from algae, mushrooms, and even milk proteins as alternatives to plastic.

- Washing machine filters and fiber-catching laundry bags can reduce the number of microfibers shed from clothing into waterways.

- Natural filtration systems, like constructed wetlands and biochar, are being tested to capture microplastics in stormwater and wastewater.

Going Beyond the Surface

Plastic pollution isn’t just what we can see—it’s hidden in our closets, cosmetics, food, and even our bodies. Change starts with awareness, but it doesn’t end there. We need continued investment in policy, innovation, and infrastructure that helps us phase out harmful plastics, hold producers accountable, and build a future that’s less toxic. By understanding the scale of hidden plastics and microplastics, we can support smarter choices—and stronger systems.