For Better or for Worse Plastics: Which Ones to Avoid

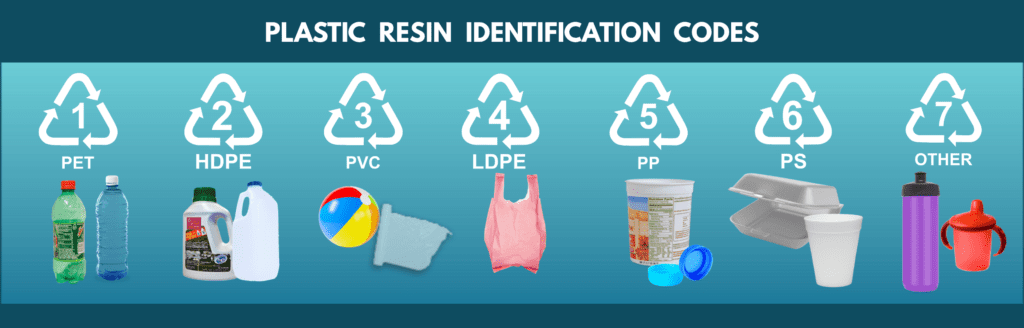

If you’ve ever flipped over a yogurt container or a takeout box, you’ve probably seen the little triangle made of arrows—the “chasing arrows” symbol—with a number inside. For many of us, it’s become shorthand for “recyclable.” Toss it in the blue bin and move on, right? Not quite. This common assumption is one of the biggest recycling myths out there.

That triangle on the bottom of your plastic bottle doesn’t actually mean it’s recyclable. It refers to the type of plastic resin used to make the product. A resin is essentially the raw, melted-down plastic material that gets molded into bottles, bags, wrappers, and clamshell containers.

The Truth About the Chasing Arrows Symbol

The Resin Identification Code (RIC) system was developed in 1988 by the Society of the Plastics Industry (now the Plastics Industry Association)—not by an environmental or governmental agency. It was originally intended to help plastics manufacturers and recyclers distinguish between different kinds of plastic, not to guide consumers on what could go in the recycling bin.

Unfortunately, the use of the “chasing arrows” symbol on plastic products has led to widespread confusion. Many plastics bearing the symbol can’t actually be recycled in most curbside programs. To address this, California passed Senate Bill 343 in 2021, banning the use of the recycling symbol on products unless they’re regularly collected and processed for recycling in the state.

The “Better” Plastics

Nearly all plastics are made from fossil fuels—primarily oil and gas—and the process of extracting them and producing plastics exacerbates both the climate crisis and public health risks. That’s why avoiding plastic whenever possible is the best choice. Still, not all plastics are equally harmful—some are considered less harmful to human health and are more commonly recyclable, especially when they’re clean and properly sorted.

- #1 PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate) bottles, tubs, jugs, jars, and clamshells: Commonly used for products like soda bottles, salad containers, berry clamshells, and some takeout boxes. Widely accepted in recycling programs.

- #2 HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene): Used in milk jugs, shampoo bottles, and detergent containers. It’s one of the most recyclable plastics.

- #5 PP (Polypropylene): Found in products like yogurt containers, hummus tubs, and margarine tubs. This plastic type is particularly hard and heat-resistant. It’s recyclable in Boulder County, but less widely accepted than #1 and #2 plastics.

See our Plastics Recycling Guide for Boulder County!

The “Worst” Plastics: Avoid When You Can

Then there are the plastics that carry bigger problems—both because they’re toxic to human health and nearly impossible to recycle.

#3 PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride)

Used in cling wrap, some food packaging, medical devices, shower curtains, and even children’s toys. #3 PVC are believed to contain carcinogens that can cause rare liver cancer, disrupt male endocrine systems, induce reproductive and birth defects, impair child development, and suppress immune systems.

#6 PS (Polystyrene, commonly referred to as Styrofoam)

Found in foam cups, to-go containers, and meat trays, as well as many red cups and black plastic containers. Lightweight and cheap, but made from styrene, a possible human carcinogen. It also lingers in the environment for centuries.

#7 PC (Polycarbonate) or sometimes labeled “Other” (the Catch-All Category)

This category is a catch-all for plastics that don’t fit into categories #1 through #6. It includes polycarbonate (PC), which often contains BPA, used in some water bottles, baby bottles (though now, thankfully, less common), 5-gallon water jugs, and can linings. It also includes a wide variety of other plastic resins and blends. Because this category covers many different materials, it’s nearly impossible to recycle and offers little to no transparency about its exact chemical makeup. Think of this as the “mystery meat” of plastic.

Black Plastics

Black plastics—like takeout containers or microwaveable trays—can contain unregulated amounts of toxic chemicals such as phthalates and flame retardants, as well as heavy metals. Black plastics with a #3, #6, or #7 have no recycling markets. Even if made from a more recyclable #5 plastic, black plastics are difficult to recycle because the dark pigment cannot be “read” by optical sorters at recycling facilities, so the plastics must be sorted manually, increasing sorting costs substantially.

Print your Quick Guide to Plastics!

Effectiveness of Policies to Reduce Single-Use Plastics

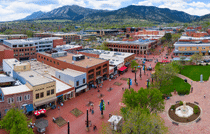

To reduce the widespread use of two of the most problematic plastics—plastic bags and foam cups and containers—Colorado passed the Plastic Pollution Reduction Act (House Bill 21-1163). This law, one of the boldest and most comprehensive plastic waste reduction laws in the country, combines two statewide bans, plus the nation’s first reversal of a plastic preemption law.

- A statewide ban on single-use plastic carryout bags at large retailers. Plastic bags are not biodegradable and are one of the most common pollutants in Colorado’s rivers and creeks, clogging waterways, leaching chemicals, and harming wildlife. In the first year of implementation, this law prevented approximately 1.5–1.8 billion plastic bags from being distributed in the state.

- A ban on polystyrene foam (commonly referred to as Styrofoam) food and beverage containers at restaurants and retail food establishments, due to its health hazards and low recyclability. Polystyrene carries serious health risks—like leaching styrene, a probable human carcinogen—and is notoriously non‑recyclable, fragmenting into harmful microplastics.

- Repeal of plastic preemption law. A preemption law is when a higher level of government (e.g., state) prohibits lower levels (e.g., cities, counties) from passing their own rules on a particular issue. In Colorado, since 1989, municipalities had been prohibited from regulating plastic products like bags or packaging. With the reversal, communities are able to take local action to further curb plastics, such as Breckenridge’s ban on the sale of single-use plastic water bottles (under 1 gallon) and single-use plastic containers and serviceware in retail food establishments, effective July 1, 2024.

Changing the System, Not Just Our Habits

Understanding which plastics pose the greatest harm—and which are more manageable—helps us make informed choices, rather than treating all plastics as equal. But avoiding the most toxic plastics isn’t something individuals can do alone—and we don’t have to accept toxic packaging and single-use waste as the norm. Smart legislation like Colorado’s Plastic Pollution Reduction Act drives real, systemic change away from a throwaway culture and toward systems where safer, more sustainable options become the standard.